BRAND VALUE STRATEGY

This is the story of one of the most colossal strategy and marketing mistakes in modern history. Previously we examined Hermès brand value and brand extension strategy. We now examine the New Coke story in the context of brand extension and introduce a few other key concepts.

The Situation

Coca-Cola was introduced in the US in the 1880s. It was the first cola product on the market and created a new category. Coke’s subsequent marketing strongly relied on an “original” position and heavily emphasized their “original” standing. In the 1940s, advertisements read, “The only thing like Coca-Cola is Coca-Cola itself. It’s the real thing.”

In 1898, Pepsi-Cola was introduced and was the only even marginal challenger to Coke’s near complete dominance of the market.

By the early 1950’s, Pepsi found it self in a position competing head-on with Coke (the industry leader by far), with no noticeable differentiation, with only about 15 percent market-share, and losing market power to Coke in terms of distribution influence, marketing budgets, etc. Brand value trajectory was on the way to zero.

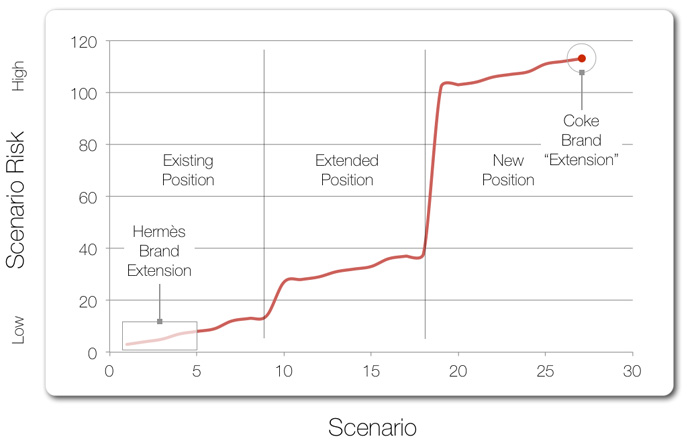

Faced with increasing marginalization and even extinction, Pepsi decided to launch a new offer to a new target with a new position. On our scale of measuring risk for brand extension, this move scores at the very top, but faced with the alternatives, it was actually no risk at all. Essentially, Pepsi was a company with no market-share and no net income with which to start over with a completely new brand and brand value concept. But they had a secret weapon.

The Secret Weapon

Strategic research and thought had been advancing in the US. Concepts of segmentation, targeting, and differentiation were relatively new ideas and, apparently, unheard of by Coke executives.

Pepsi chose to re-position itself as a youth brand; it narrowed its focus with a slightly sweeter product more appealing to a younger demographic. In essence, their secret weapon was differentiating for a narrower demographic than the entire market.

By maintaining and carefully and consistently investing in its new position and maintaining focus on its new target, Pepsi began to gain ground. The marketing was consistent and persistent. In the 1970s, it secretly conducted blind taste tests and, finding a significant advantage, publicly launched the Pepsi Challenge where it regularly won in blind taste tests.

In the 1980s, it began a worldwide tour of the Pepsi Challenge and later announced that the “Pepsi Generation” had arrived. Market share continued to grow and the fierce marketing battles between the two companies brought even more attention to the segment, increasing its overall size significantly.

Why was this happening?

The powerful, positive trends had been set in motion and maintained by Pepsi through relentless, unblinking focus on maintenance of its existing position, dedication to its target, and refusal to dilute energy by adding new offers to a segment that had little “elbow room” to start with.

Coke’s market share in the soda segment dropped to a record low of 24 percent in the early 1980s – still the leader, but with Pepsi close behind in number two position, and Diet Pepsi in number three.

Some analysts say the market was reaching a new equilibrium with Coke owning the older demographic segment and Pepsi the clear leaders of the younger demographic segment.

Off the Risk Scale

But Coke panicked and began shelling out millions of dollars to an army of hot-air consultants.

In a growing market with a likely stabilizing market-share, the solution dreamed up by the consultants (strategists the world over shook their bowed heads at) was for Coke to:

- Abandon its position as the “real thing”

- Abandon its loyal target that was increasing polarized against Pepsi

- Abandon its market-leading offer

- Go head-to-head with the market leader (Pepsi in the youth segment)…

- …with a new untested position

- …focused on a new hostile target

- …with a new offer, and (sigh)

- …NO differentiation

Regarding the abandonment of its original position one analyst said, “How can you bring a new real thing? It’s like bringing a new God.”

With its “new real thing”, Coke was essentially telling consumers that for the past 20 years they had “missed the boat” and been making the wrong decision.

Competitive Response

In response to the announcement of New Coke by Coke executives, Pepsi’s CEO declared at his own press conference that, “The cola wars are over. We won.”

Then he announced a company wide holiday in celebration.

Your competitors will not sit idly by while you manoeuvre.

Off the Sanity Scale

Coke’s “strategy” involved new position (the riskiest), new target (second riskiest) and new offer (third riskiest). On the Extension Risk scale, this approach scores 113, the highest figure.

Let’s take a look…

Not Bad Enough

Most people would agree that choosing the riskiest strategy possible would be bad enough, but not for Coca-Cola.

First, it chose to enter a market behind a leader and with no differentiation. Despite the fact that Thierry Hermès at least seemed to understand this concept in 1837, and Pepsi had clearly understood it in the 1950s, Coke executives in 1985 seemed unable to grasp it.

Second, Coke did not just make a line extension. It also slaughtered its global, market-leading offer. This was done due to distribution-related issues. Shelf-space itself is a war that supermarket brands wage against one another, and Pepsi had gained a lot of ground in this arena, reducing Coke’s available shelf space. Splitting shelf space between two of its own competing brands was not considered feasible, nor would be the increased distribution, inventory and marketing costs.

Lastly, not only did Coke choose to pursue a new target (the second riskiest approach), but it chose to pursue a noticeably hostile new target, made so in part by the previous polarizing marketing approaches of both Coke and Pepsi.

The Result

The result was, in a word, unsurprisingly, “disaster.”

Not only was this entire debacle destined to utter failure purely on strategic principles, but also Coke had dramatically underestimated the loyalty of its original target to the original offer and original position – a treble failure (beyond all the other failures of basic strategic understanding).

New Coke was introduced on 23 April 1985. Production of the original coke was halted within the week. And thus began the BOYCOTT of New Coke by the original target demographic. Intense media coverage fuelled increasing outrage; protests outside company headquarters in Atlanta garnered more negative press. Disgusted, Coke drinkers switched en masse to Pepsi.

Retreat

On 11 July 1985, less than two months after the launch of New Coke, the company CEO called a press conference and said, “We have heard you.” Then he turned the press conference over to the COO to announce the return of the original Coke.

Lessons Learned (or Not)

Strategy is often viewed as an abstract science, but it is not. It is a reflection of basic human nature set into the context of a commercial environment. Hermès brand strategy and brand extension strategy took these factors into account, while New Coke did not. One cannot succeed while ignoring basic human nature.

Stories like the one above unfortunately abound because basic strategic principles are ignored.

In the 1960s IBM was one of the most profitable large companies making more or less one product, mainframe computers.

By 1991, IBM had extended their brand to include workstations, midrange computers, pen computers, personal computers, software, telephones and networks. By then, its revenues were 65,000,000,000 US dollars. Its losses were 8,000,000 US dollars…per day.

Brand extension is a critically important tool, but it must be used judiciously, thoughtfully, carefully and with proper analysis before it is executed.

The key points to keep in mind are:

Extend offers that add value to existing targets and that are based on existing position

Create new offers only after careful research

Extend targets as long as they align well with existing targets and with existing offers and can extract value from an existing position

Approach new targets with extreme care, research, testing and due diligence

Avoid, if at all possible, extending an existing successful position

Unless the ship is sinking, do not create new positions

Follow the Hermès brand value and brand extension strategies